That the Committee produced so little in competitive long-distance events was not entirely their fault. Their work-force consisted of half a dozen enthusiastic volunteers and the majority of their effort went into the creation of the race-track at Langa Langa, which during 1951 and 1952 provided many days of excitement and entertainment for the East African motoring fraternity. Red tape was just as sticky in the 1950s as it is now, and no one was able to devote the necessary time to get the more ambitious ideas moving. Even the administrative work involved in maintaining the race-track at Langa Langa eventually necessitated taking on a part-time Competitions Secretary on an honorarium.

But one very much more important factor was acting as a b eke on progress of motor sports in the Colony, and that was the increasingly serious security situation. A State of Emergency was declared in Kenya on 20th October, 1952, and it seemed unlikely that there was much immediate future for long-distance competitive motor sport.

Against this background of frustration and disappointment for would-be competitors, the much-quoted conversation took place between a member of the Competitions Committee, Erie Cecil, and his cousin Neil Vincent. Vincent was a dedicated motor sportsman, but try as they may, nobody could persuade him to compete at Langa Langa. “I can imagine nothing more boring than driving round and round the same piece of track. ” When urged to describe what would be to him an exciting event, he thought for a while and said “it would be one which covers a large mileage across all kinds of African roads. Slam the door and the first man home is the winner.”

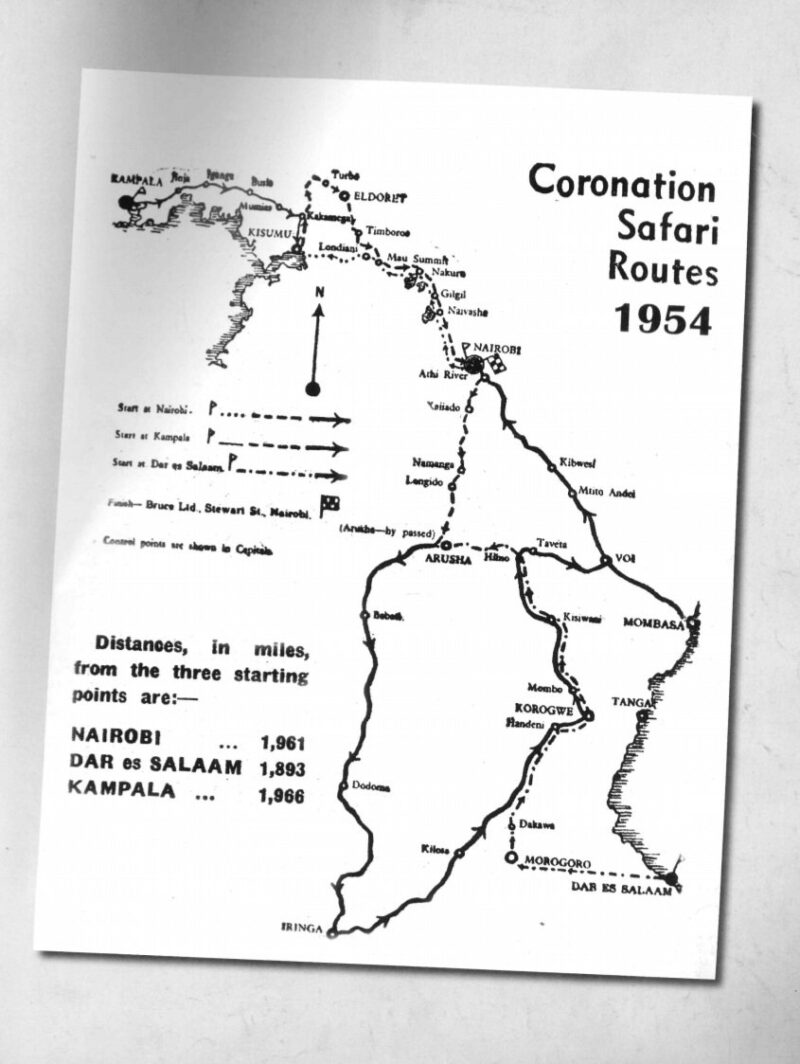

There it was again – the same old longing for a long-distance, open road competition. Not a new song, but a haunting refrain that would not go away. Cecil and other enthusiasts such as Ian Craigie, the Competitions Secretary, pondered the problem of how to succeed where so many others had failed. Question: How to get the necessary administrative co-operation from territories outside East Africa? Answer: Don’t try. Keep the rally within the East African territories and thus have to deal with only one absolute authority, the Royal East African Automobile Association. A route starting and finishing in Nairobi and circumnavigating Lake Victoria in either a clockwise or anticlockwise direction was considered most suitable, with Controls at Jinja, Bukoba and Mwanza. Question: How to get the idea approved by the ‘establishment’ of the REAAA and the Competitions Committee, particularly in the difficult security situation prevailing? Answer: Appeal to the colonial establishment’s strong ties with the home country and the monarchy by making the event a tribute from the motoring public of East Africa to the young Queen Elizabeth II on the occasion of her forthcoming Coronation on June 2nd 1953.

The idea worked, and approval in principle was given by the REAAA. The matter was taken to the Committee, Colonel Manton suggested a name for the fledgling event, and Minute 115 of a meeting held on 21st January 1953 states:

“Coronation Safari: The question of a race from Nairobi round Lake Victoria and back was discussed, and the following points approved:

(a) The event shall be called the Coronation Safari, and for obvious reasons it was not to be suggested that the event was an out-and-out race, but would rather be on the lines that the event was a reliability trial.

(b) The Chairman (Colonel Manton) would send off a letter to all parties likely to be interested, but using care as to the wording of such a letter, bearing in mind the uncertain state of the country at this moment. Such a letter would in the first instance be sent to the trade and oil and tyre companies, with a view to obtaining their reactions as to support by them of such an event.